Another day, another extract from the pages of The Road Book which depicts the Giro d'Italia in all its gorgeous glory. Today we have a brilliantly tender and touching piece by Gino Cervi from The Road Book 2011. Gino walks us through the magnitude of the Giro for the people of Italy, from an Italian's perspective, before penning a thoughtful ode to Wouter Weyland, who tragically passed away after a heavy fall on stage 3 of the 2011 edition of the corsa rosa.

Birds of a Feather by Gino Cervi: an extract from The Road Book 2011

Italy is a young nation. Just over 160 years old, it is junior compared to fellow European countries that have ‘political’ stories spanning centuries. The monarchies of France, England and Spain have been around since the Middle Ages when Italy was a colourful mosaic of towns, communes, lords and statelets, often warring with one another. It took the Risorgimento – Unification of Italy – and the mid-1850s Wars of Independence for Italy to take form as a state rather than merely being ‘a geographical expression’, as Prince Metternich, chancellor of the Austrian Empire, contemptuously called it in 1847.

But even when Italy finally became a unified entity in 1861, it soon became clear that to build a country, it wasn’t enough to draw borders, adopt one flag – the tricolore – and to have a sovereign (Victor Emmanuel II) recognised as the king. It needed different people, cultures, languages and traditions to fill that ‘geographical expression’ with history, with common actions. No small thing. It was around then that a post-Risorgimento motto began to spread and become famous: ‘Fatta l’Italia, ora bisogna fare gli italiani’ (‘We’ve made Italy, now we must make Italians’).

The Giro d’Italia undoubtedly had an important hand in ‘making Italians’ and shaping the country’s collective identity. Invented in 1909, when Italy was a middle-aged signora, the corsa rosa – which, to be fair, would only become ‘pink’ from 1931, when it introduced that dazzling leader’s jersey – has become part of that heritage of shared traditions that, for a people, are deeply rooted across the board, ignoring class or social standing, alongside things like the music of Giuseppe Verdi, pizza, coffee.

The Giro has become a collective ritual, a nigh-uninterrupted reference point in our memory, only stopped for national emergencies like the two World Wars. Even the Giro itself has become aware of its own function and cultural identity. Since the first edition, the organisation distributes to its entourage – teams, journalists, sponsors – an Atlas of an official programme. It’s a kind of guidebook that records all the official technical data of the race: route layouts, altimetry, timetables, road conditions. But also for more curious readers – or perhaps, more distracted ones – useful tourist information about the territories the race passes through. Since the Second World War, this precious booklet was rebaptised with the nickname ‘the Garibaldi’. Just like the Risorgimento hero Giuseppe, it holds Italy together, from Palermo in the south to Aosta in the north, in the form of colourful maps, stage profiles, phone numbers and handy addresses for the traveller-follower.

There have also been a few special editions in which the Giro route paid explicit homage to the country’s history. The first was on the centenary of Italy’s unification in 1961, when the race director Vincenzo Torriani plotted a pilgrimage to the key places of the Risorgimento and Wars of Independence. It started in Turin, Italy’s first capital, with a stage divided into three city circuits, named White, Red and Green, then a finish in Quarto dei Mille, where Garibaldi’s expedition to Sicily embarked. For the first time in race history, the race toured Sardinia, visiting Cagliari, Palermo and Marsala. Back on the mainland, there were other meaningful stops: Teano, where Garibaldi and King Victor Emmanuel II met, the two other capitals Florence and Rome, up to Trieste and Vittorio Veneto, the last ‘conquests’ of the First World War. An outsider, Arnaldo Pambianco, won that race, surprisingly getting the better of overwhelming favourite Jacques Anquetil.

The same intention to celebrate the 150th anniversary of the Risorgimento crafted the route of the 2011 Giro. The race rolled out from the Savoy palace of Venaria Reale to cross the finish line in Turin’s Piazza Vittorio Veneto, overlooking the banks of the Po...

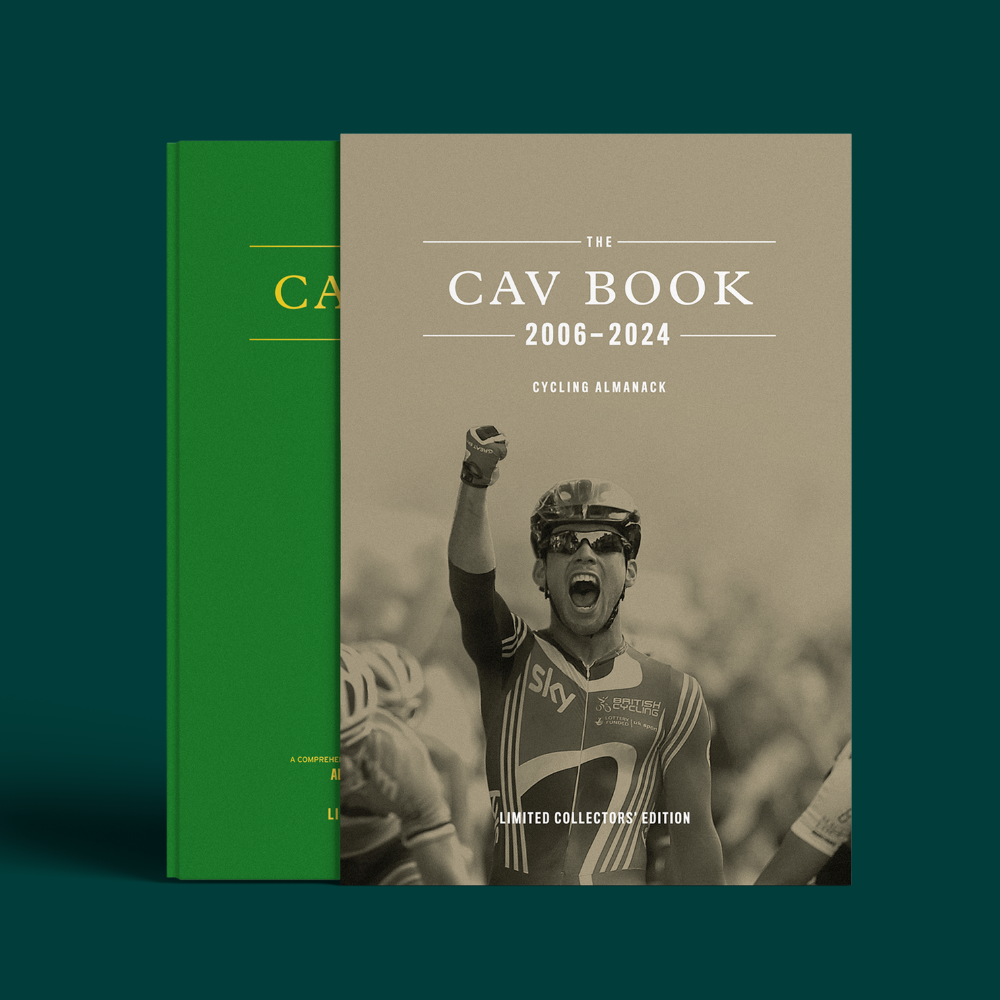

You can read the rest of Gino's wonderful piece in the pages of The Road Book 2011. We hope you've been enjoying both the Giro, and our little preview articles. Join The Road Book Society by signing up here to get all the latest Road Book news, including a very special little project we've been working on...

Illustration by Matthew Green

Images Courtesy of Graham Watson